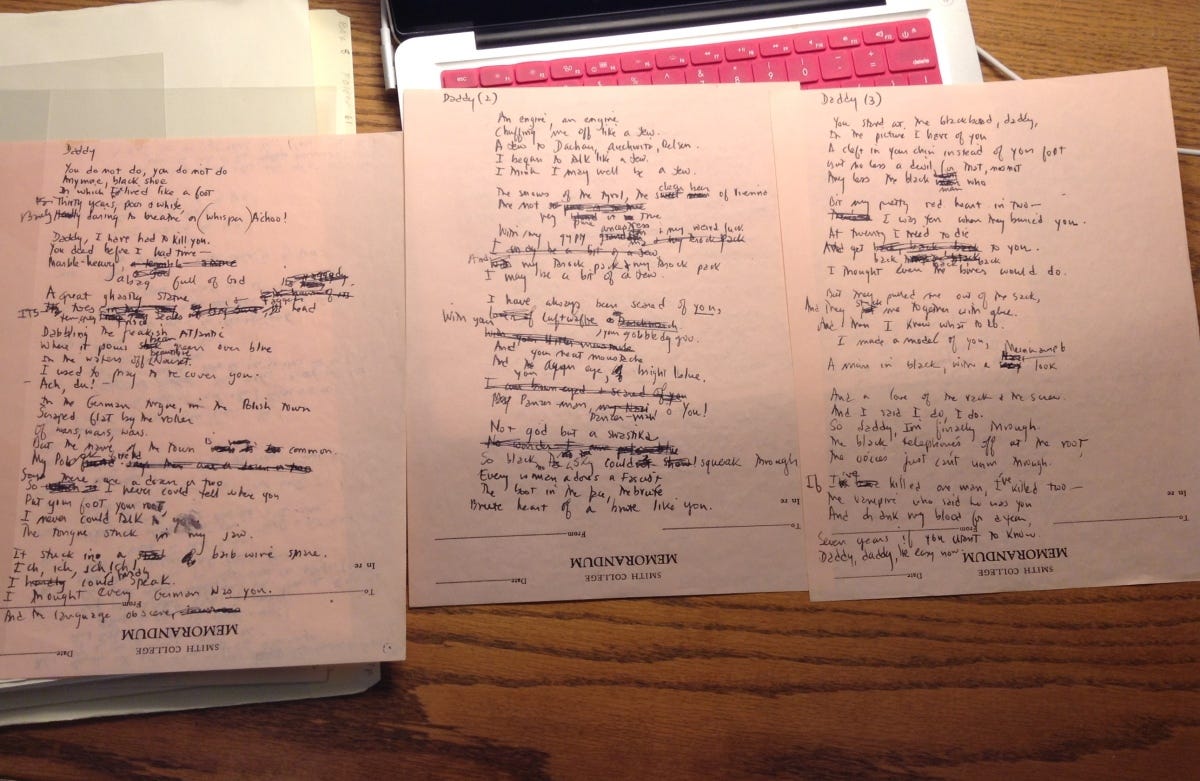

[Image description: drafts of Plath’s poem “Daddy” on Smith College pink memorandum paper. Photo credit: Sina Queryas]

It’s anathema in literary studies to claim we know how our subjects, distant and usually long dead, might have responded to our world. We’re not supposed to engage in “presentism,” to apply a modern-day lens to their lives. We kill ourselves to learn everything we can about their day-to-day lives, immerse ourselves in the literature and politics of the day, so that we might put everything in its proper context.

In the case of Plath, because she was such a fastidious recorder of the minutiae of her life, whole essays are written about her grocery lists and hygienic routines, how often she and Hughes had sex. But we’re taught that to imagine a world where Plath survived or even thrived is a bridge too far. We have to work within her life’s confines— the biographical version of New Criticism, with Plath as the text.

Because I have never had any talent for rule-following, I have never been able to do this. Speculation is the name of the game for me, because without it, I (and so many of my colleagues) would have long ago accepted the bad ideas we were handed about who Plath was without question, and a more nuanced and complex reality of her life and work might never have emerged.

I root my work on Plath in imagination as a source of shared hope for a different world. This is a political act inspired by writers like Arundhati Roy, with her famous call to action: “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” In this spirit, I want to share a letter I helped to write with some of my beloved colleagues, and which I am grateful to Literary Hub for publishing, swiftly.

Because it past time to speak as loudly as possible against the kidnapping and deportation of student activists in this country. It is past time to refuse our complicity in the Israeli-American genocide of Palestine. It is past time to push your deans, your presidents, your bosses, your spouses, your siblings, your parents, your best friends to do the same. If you have a voice, you have to use it, now. This is the bare minimum. This is the least we can do.

This is what Sylvia Plath would do. We don’t need to wonder what Plath’s politics were— she was openly progressive with a burgeoning radical consciousness that would only have advanced, had she lived. For anyone who wants to argue, let me say: The woman who wrote “Daddy” and loudly decried American nuclear power and McCarthyism at the age of 17 would not be squeamish about calling out genocide and fascism. There would be no false equivocations from Sylvia Plath.

Plath’s most famous poem, “Daddy,” openly invokes and roundly rejects fascism. She refuses to go along with a system that co-opts art and love into fetishized violence. The poem ends as she rallies the villagers to her cause. They help her to kill fascism dead in its tracks. And when they do, she is “through,” as in, she is over, across, free. At least until it returns like the hydra it is, at which point, we know what to do. Because she told us how to do it: Band together. Use all your poetry and song and laughter and rage. Kill it dead. Drive a stake through its heart. Stamp it out and dance for joy.

Plath did not believe that her art was in any way separate from her politics, which is why her politics took the lasting public form of her art. And this is why we need to stop buying into any voice inside or outside of us which hints that we should be quiet, because this doesn’t involve us. Because we are “only” poets or “only” literature scholars or “only” fans. No art exists in a vacuum. All art is a vital product of its world. So if you make art, or you love it, you have to stand up against a country hellbent on destroying the creative solidarity that builds a better world, a world free of state-sanctioned murder and the violent repression of speech.

Do you think your art, or the art you love, will be spared, under fascism? And even if it is— can you still love it? What is that love worth? How will we face what is left to us? How will we face ourselves?

Emily, did you ever see Warren Plath's obituary? He said he was glad not to die while Trump was president and asked for donations to Planned Parenthood. Imagine what SP would have been up to if that's her brother!

The thing about "Daddy," which is a poem I taught for years is the cadence it imposes. Much like a death march.