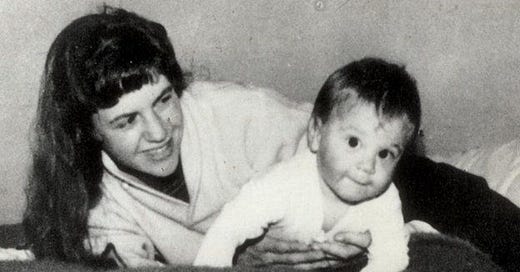

[Image: Sylvia Plath holds her infant son, Nicholas Hughes, in 1962. They are both smiling.]

Dear Plathians,

I write to you from my dining room. I’ve just put the big kids on the bus and the baby, just over five months, is still sleeping after I nursed him at 6:30 this morning.

I’m so tired. I even tweeted about how tired I am, which is just plain dull, but what is Twitter, sometimes, if not a sounding board for the worst of us: boring, greasy-haired, about to clean up cat pee and eat soggy Muesli for the fourth morning in a row?

I’ve been thinking about Plath and her “still, blue hour,” which is how she described the time when she wrote her great Ariel poems in the fall of 1962, the ones she so correctly predicted in a letter to her mother would “make [her] name.” They did make her name. Sometimes I quote that letter to my students: “I am a genius of a writer, I have it in me. I am writing the best poems of my life. They will make my name.” It’s hard for me to say it all out loud without breaking down; writing it, I feel hot tears prick at my eyes (and now, from elsewhere, the baby cries, and because I am no genius, his cry will not melt into any walls, but force my attention from this place of writing, which is no place at all).

Plath’s letter to her mother moves me without fail because, as I began to age with her (marriage, babies, marriage disaster, divorce, single motherhood), I felt I knew what she was up against, writing those poems, in a way no biographer had ever really understood or gotten down on the page. There is a thing I learned, in my 30s— you can know something intellectually, know it as an abstract fact, but that doesn’t mean much until you learn it emotionally. Before my 30s, I knew Plath’s life story (or thought I did) like the proverbial back of my hand: here is her time at Smith (I type away and the little blue veins run up my hands like rivers) all tartans and cardigan sweaters and breakdown; here is her time in London (see how the fingers bend at the knuckle base, mimic the way I was taught to play piano) bathing Frieda in a Pyrex bowl, discovering the cracks in her marriage as surely as I see the 41-year old skin over the 41-year old bones of my hands dry out and crack no matter how often I apply a salve.

It’s in the London of 1961 that the Hugheses marriage really gets hit for the first time, the London of 1961 where, Plath later claims in a 1962 letter to her therapist, Hughes beats her and she miscarries their second child. Plath writes nothing of this event anywhere else (although Hughes does, but that’s a topic in my book), but she does write the poem “Parliament Hill Fields,” about the miscarriage. “Your absence is inconspicuous,” she writes. “Nobody can tell what I lack.” She’s writing about the lost pregnancy, of course— but it strikes me that maybe she is also writing about other losses, other dreams that have been taken from her, and which no one can see in the figure of a 28-year old middle class woman walking through Parliament Hill Fields. Maybe she doesn’t just lack her pregnancy. Maybe she lacks her faith in the marriage that once sustained her; or anyway, maybe this poem is the beginning of that lack of faith. Critics in the 1970s, reading Plath’s poetry for the first time, were keen to point out that she seemed obsessed with alienating herself from nature (as though it was her job as a poet to do otherwise, I guess?), but in “Parliament Hill Fields,” I read the work of a woman who understands her body as mimicking the great world around her, where, “Faceless and pale as china/The round sky goes on minding its business…”. In that image, I see the inner workings of a woman’s womb which, to a baby housed within, would be the sky and would, regardless of the fate of its inhabitant, regardless of the way that fate brought harm or not to the owner of the womb, go on, minding its business. At the end of the poem, the speaker enters a lit house. And although she enters the light, she is “take[n]” “to wife” by, “the old dregs, the old difficulties.” This is the tension that electrifies Plath’s journals: she wants to hole up and write and pretend the outside world is nowhere, is dead, but without the outside world, what is there to write about? In “Parliament Hill Fields,” in a neat inversion, the black of the fields and the melting city she stalks are the poet’s interiority; the lit house she enters is life, which, while it might be the dregs, she enters, and willingly. From that tension, a great poem arises.

Here, in the New Jersey of 2021, it’s a rainy April morning in what I hope is the last stretch of a deadly pandemic. Each room in my house now feels like those dregs, those difficulties, and they take me, day and night, to wife. The baby won’t sleep anywhere but on or near his father or me. We co-sleep, which means, (ha), no sleep. The older children, unable to go almost anywhere, still, litter the house with toys and wrappers and laundry. I think of Plath, alone in her creaking old country house in Devon, rising at 4 am to write, battling heartbreak and sickness and rage, riding the heartbreak and sickness and rage into those poems. I think of Jane Kenyon, who supposedly said something like, Let me fold another load of laundry before I ever complain about my life. I think of Marina Tsvetaeva, who, conversely, said something like, To never sweep another floor— that is my idea of heaven. I think of my mother, who went to Florida the day after Easter, and left the pan with the leg of lamb grease to soak in the kitchen sink and, when she returned a week later, discovered it still sitting there, my father ignoring its presence, ignoring its pooling fat, turning rancid, for the entirety of a week. Seven days and seven nights and that greasy pan never once called out to him, never once sucked him in with its filthy song. Sylvia wrote in “Mary’s Song,” “The Sunday lamb cracks in its fat,” then managed to turn a joint of meat into the whole entire world, a world that was both her inter- and exteriority: It is a heart/This Holocaust I walk in. This house in New Jersey has become my whole heart, my whole holocaust: this suburban place safe from the horrors of the country where I live, and the shame I bear in its name, in my white skin. My Twitter friend Amber wrote to me a while back that she was excited to read my book because it was a book by a mother, writing about Plath, and it is. I am. This morning, I close my eyes and think I can feel her with my whole heart which, if I let it (and I do) will swell and fill until I think I’ll collapse beneath its weight. Plath’s genius was, she let her heart expand until the world was her heart, her heart the world: it was a brand new place she could walk through. When she wrote those poems in her still, blue hour, against all odds, she let us walk beside her.

we all owe her so much for telling the truth about marriage & motherhood. what's sold to us is some real B.S. i'm grateful for you & others who continue to break the spell of all the promises.

Just...wonderful. Will be thinking on this.