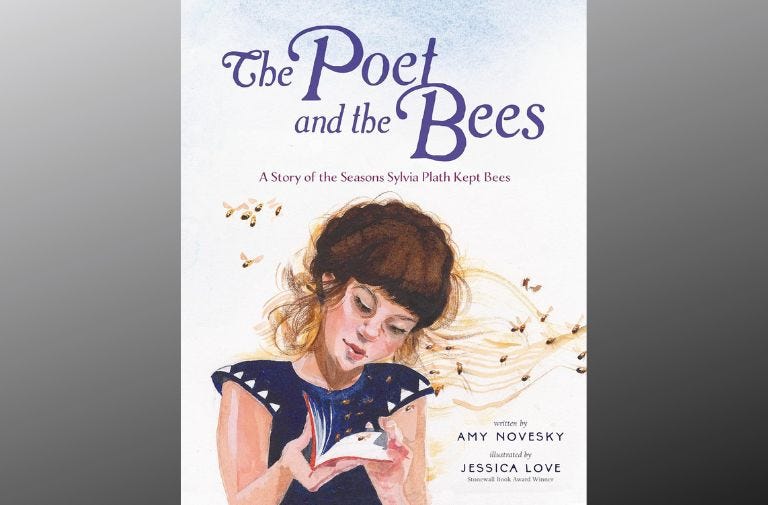

Last spring, I came across The Poet and the Bees: A Story of the Season Sylvia Plath Kept Bees (Viking, 2025) a children’s book written in verse, by the poet and writer Amy Novesky (illustrations by Jessica Love). I could not believe it had been out for several months and I had somehow missed it.

I have read so many fictitious interpretations of Plath’s life that miss the mark— but this book is the real thing. It manages to introduce children to Sylvia Plath’s last year on the earth without shying away from difficulty or glossing over hard truths. I loved it, and immediately reached out to Amy to see if she was willing to talk more with me about Plath, bees, and poetry.

I’m delighted she agreed. Check out our interview below, and be sure to get a copy of The Poet and the Bees, or one of Novesky’s excellent books about women like Frida Kahlo, Billie Holiday, and many others.

EVD: You write in the biographical note at the end of The Poet and the Bees that because you knew Plath had killed herself, you avoided reading her work; it frightened you. Can you tell me why that frightened you?

AN: When I was a young, deeply sensitive and sheltered writer first encountering Plath’s work it frightened me, as I was new and naive to the world and its heartbreaks. I felt all I felt, which was a lot. I couldn’t relate because I didn’t want to. Or, maybe it’s that I could. Now that I’m older, heartbrokened-in, and hopefully a bit less naïve about the world, I’ve gotten better at looking at things and finding the truth and beauty of it all.

That Sylvia took her life and the manner in which she did is still deeply unsettling to me. She was 30 years old. I remember being thirty. Thirty is young, too young. And, Sylvia was so full of life and love, anger, grief. She had so much still to write, so much growing up to do and life to live, not to mention babies to raise. Her death is shocking to me even if it was not surprising.

EVD: Was that fear still present in the composition of The Poet and the Bees, and did it show up in the text? If not, how did you resolve it? What changed?

AN: Such an interesting question. Yes, I am sure it is there. It is there, if not in the foreshadowing of her impending death, then in the literal handling of bees and the fear that beekeeping elicits: fear of being swarmed, fear of getting stung. These are legitimate fears. And so, yes, it is in the story itself in the bee theme. Like Sylvia, I kept bees. I’ve been swarmed. I’ve been stung. I felt fright. I felt pain. And I realized I could.

And then, we know the ending of this story, and all stories. Sylvia can find joy in the seasons, her flowers, her bees, her jars of honey, her children. She can dream about all she will do—Winter on a wild coast. Drink honey-colored whiskey. Write something funny. Move to London, live in a famous poet’s flat. Paint the walls early-morning blue, yellow, and lilac. Finish her book of poems. And yet. We know this is Sylvia’s last year alive, that she won’t make it to spring (she died in the middle of winter), and that’s what gives her story, this story, every story, its poignancy.

EVD: For obvious reasons, Sylvia Plath is not traditionally understood as a subject for children’s literature. I don’t agree with this estimation, and (of course) you don’t, either. Can you tell me how you found a framework to tell a chapter of Plath’s life in a way that children will respond to?

AN: I’ve always approached my stories more like a poet, focusing in on a moment, a detail, a footnote, and try my best to evoke, spare and poetically, a life through language and imagery.

Writing about Sylvia’s experience keeping bees felt most authentic to me, as, at the time I was researching and writing the book I was keeping bees. I had a personal connection to the story, which is essential to me and hopefully translates to a young reader connecting to the story.

I think, too, this story is as much about emotions. How to feel these big things. How to feel safe around them and how to survive them, how to thrive despite them. She is just a poet who keeps bees. She is covered in stings. She feels all she feels, which is a lot. I think that that is a very relatable, universal theme for young people.

And then, the seasonal framework was a natural, given that it’s a theme in Sylvia’s work, and in beekeeping, itself. And, it is a fairly common structure in books for young readers, this meaningful and comforting repetition of time and attending to and connecting deeply with the natural world.

EVD: Plath’s “bee poems,” as well as several other poems from her book Ariel, are beautifully echoed and woven throughout your text. How did you manage to strike a balance so that your work is informed by Plath, yet still wholly original?

AN: Thank you! Once I hit upon the bee theme and the seasonal structure, the writing itself flowed, which was fun, which is rare! I believe my experience as a writer, mother, and beekeeper informed the writing, and that balance, for sure. And, it is my voice; it is how I write. In short, this story has as much of me in it as Sylvia.

That said, I wanted to make sure to evoke Sylvia’s—if not voice—cadence. One way I did this was through Plathian repetition: pom, pom (from “The Swarm”); dust, dust; dust; poem, poem, poem (my own); sweetness, sweetness (from “Wintering”). And then, yes, I very cautiously and sparingly wove in a few of her own words and phrases, both from poems and letters, throughout my own, including: Love, love (from “The Couriers”); like mad; the word scarves (from “The Bee Meeting”) to describe the specific way smoke moves; glowing as if lit from within (from “Blackberrying”); she is flying (from “Stings”); and, of course, spring (from “Wintering”).

EVD: How long have you kept bees? Does the practice inspire your work beyond this book?

AN: I’ve lived among bees and beehives for nearly as long as I’ve lived in Sausalito, for nearly 25 years. But I only kept bees for about five years, notably over the pandemic; it was one of the things that not only felled me—I am moderately allergic to bee venom and have been stung very badly, once on the forehead which swelled my eyes shut for a week—but got me through it. I spent hours quietly watching the bees come and go. Tell me, what else should I have done, to quote another poet.

I was taught how to keep bees, among many other things, by a pair of beloved neighbors—the word neighbors doesn’t nearly define who these two women are to me, my husband, and our teenaged son, Quinn. Great aunties, fairy godmothers (they would hate that term), guardians. They are simply, family for better for worse. When Susan died unexpectedly in 2023, our bees followed. It is tradition in beekeeping to tell the bees when their keeper has died. And, it is believed that bees accompany the spirits of the dead to the afterworld. I numbly tended the bees in my state of grief that summer and into the fall. The bees did not survive the winter, which is not unusual. After that season, I haven’t had the heart to keep bees again. I miss my friend and them every day. This book is dedicated to her.

Beekeeping taught me that I could face my fears, literally sit with them, be surrounded by them, and get stung by them. Facing your fears doesn’t make them go away, and it certainly doesn’t protect you from the worst ones coming true. Quinn and I were at Susan’s side when she died. (She was at Quinn’s birth). The initial shock and sting of it has worn off, and the faint throb of it remains. And somehow, I am able to bear it.

One little wonderful extraordinary honeybee only lives a matter of weeks; they work themselves to death, their wings becoming so ragged they are no longer able to take to air. And in that brief lifetime, that one bee produces but 1/12 teaspoon of honey.

I have my honey, several jars of it, each marked with the year it was harvested. Some I suspect I will never have the heart to eat. I want to keep that year forever. In the meantime, I have found another outlet for facing my fears: riding horses! Sitting atop a thousand-pound spooky unpredictable manifestation of it. I wrote a book about that, too.

EVD: Do you have a favorite Sylvia Plath poem? If so, what do you love about it? Does it appear in The Poet and the Bees?

AN: Wintering. It is one of the bee poems and the original, final poem in Ariel, Plath’s final book. The Poet and the Bees follows the seasons in the final year of her life, ending with winter, inspired by the poem. Ariel begins with the word “Love” and ends with the word “Spring.” The Poet and the Bees does, too.

I love this poem because it is and: it is winter and it is spring, death and life, darkness and light, grief and joy; it is hope. I love the line: I have my honey. And: This is the time of hanging on for the bees which is one of the few, full lines I quoted in my book. (I am just realizing that I misquoted it! I wrote “for hanging on for the bees”…).

I also really love this stanza from “Stings”: Of winged, unmiraculous women,/Honey-drudgers./I am no drudge/Though for years I have eaten dust/And dried plates with my dense hair.

Here’s to winged, unmiraculous women!

EVD: You have said that your books are children’s books not quite for children. I hear you—but I joyfully disagree. I was a child who detested (and always detected) being lied to, and The Poet and the Bees tells beautiful, difficult truths so that children can understand and relate to them. What are some strategies you use to achieve this?

AN: Thank you. Honestly, I just write about what I love and I write how I want to write and as best and as truthfully as I can.

I no longer shy away from tough stuff. I find it’s not only a good challenge, but a meaningful one. Life is good and beautiful and fucked up and dark and funny, sad and extraordinary and true. Shouldn’t books for young readers be, as well?

One of my favorite quotes is E.B. White’s “All that I hope to say in books, all that I ever hope to say, is that I love the world.”

More specifically, in all my biographically-inspired stories I do my best to reduce the text with rich factual details as well as subtle (or perhaps not so subtle) allusions only one familiar with the subject and/or a scholar (like you!) would catch. In other words, young readers won’t likely pick up on everything I write, but maybe their parent or an older reader will. This allows the story to work on multiple levels and for me, the author, to write for all ages, which I think the best picture books are.

EVD: What are you working on next?

AN: I have a picture book forthcoming called TO WANDER, an ode to and metaphor of travel, not only around the world and, simply, one’s neighborhood or backyard, but through life. It will be published by Viking in 2027.

Amy Novesky is an author, book editor-at-large, Language Arts teacher, equestrian, and a poet who keeps bees. In addition to THE POET AND THE BEES, her books include IF YOU WANT TO RIDE A HORSE; GIRL ON A MOTORCYCLE; and CLOTH LULLABY, THE WOVEN LIFE OF LOUISE BOURGEOIS. To come is TO WANDER, an ode to travel of all kinds, arriving spring, 2027. Amy lives just north of San Francisco. To kearn more about her and her books, visit www.amynovesky.com.

Thank you, Emily, and Loving Sylvia Plath readers!