Sylvia Plath & Mean Girls

Today is October 3, or, in Internet-Land, “Mean Girls Day.” So-called because, in the 2004 movie of the same name, the heroine Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) tells the audience, “On October 3, he asked me what day it was.” She’s talking about Aaron Samuels (Jonathan Bennett), the hunky love interest of at least two of the film’s main characters. As Cady’s voiceover narrates their budding flirtation, the camera cuts to Aaron turning to Cady. She says, “It’s October 3,” and smiles dreamily as her crush turns back to his math homework.

Sylvia Plath was born in October but died in 1963, so she never got to witness the phenomenon of this cult classic (we recently showed it to our 12-year-old daughter; trust me, it holds up). Sylvia would have related to Cady, who, despite being the brightest student in her math class, pretends not to understand the lessons so she can score after-school tutoring sessions with Aaron. In one scene, he “explains” the problems to her. Cady wills a dim-witted look of flirty gratitude onto her face as her voiceover says, “Wrong. Wrong!” Heather Clark’s landmark 2020 biography Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath quotes Sylvia’s scrapbook after losing a spelling bee in 1947: “‘I was glad that Bill got first prize because I always like having a boy ahead of me!’ She repeated the sentiment in her diary: ‘I had hoped he would win, for its [sic] always nice to have a boy ahead.’” In her introduction to Letters Home, a volume of Sylvia’s letters to family from her time at college until her death in London, her mother Aurelia described how her daughter had to stop dating boys with literary ambitions— they were too jealous of Sylvia’s impressive string of publications, which she had racked up even in high school, “inject[ing] a sour note in the relationship.

Mean Girls highlights the general absurdity of changing yourself to fit into a socially prescribed role, but focuses on the ways young women tear themselves and one another to pieces over heteronormative romance— sometimes literally. In another famous scene, Cady and her nonconformist friend Janice Ian (Lizzie Caplan) plot to bring down Regina George (Rachel McAdams), the head of the clique “The Plastics,” and the most popular girl in school, someone Janice calls “a life-ruiner.” They sneak into Regina’s locker during gym class and cut holes in the breasts of her white tank top. Regina, as indefatigable as Sylvia’s hoof-taps, glances down at the holes, which now display her hot pink bra, shrugs, and walks out into the hallway. The next day, every girl in school sports a brightly-colored bra through her holey white tank top.

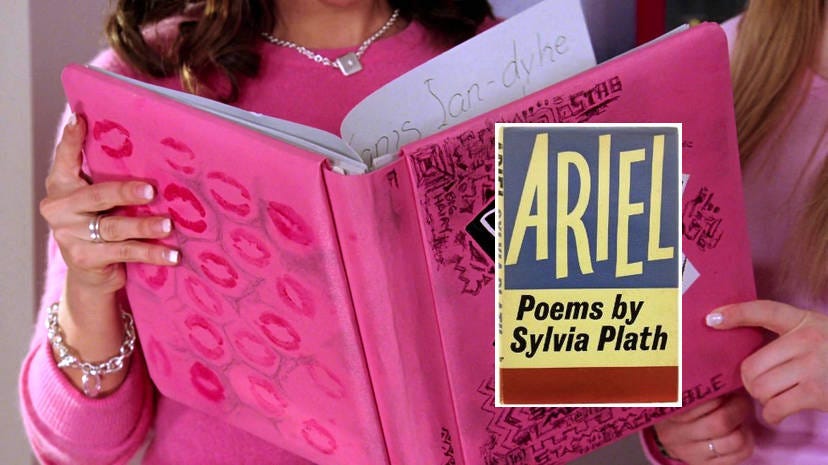

Sylvia became a kind of literary Regina George after she died. “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus” were the poetic equivalent of hot-pink-tits-through-the-white-tank-top, with hordes of young writers inspired to scribble their version of youthful angst in their journals. And while Plath’s original poems, which spawned so many imitators and detractors, weren’t, like Regina George’s accidental fashion statement, the result of a subterfuge, they did enter the world outside of the context in which she had prepared them, when Ted Hughes published a version of Plath’s book Ariel that looked nothing like the one she’d written. But, while I have thought much and written some about the problematics of that thorny history, for the purposes of this newsletter, I’ll just imagine Sylvia strolling the Valhalla of literary fame, hot-pink-tits-out, shrugging off the haters.

In life, Sylvia was tough, but she was no typical mean girl, especially not in high school, when she was, to use her own words to her mother, “a greasy grind.” In death, though, she got herself the rep to end all reps: the Joan Crawford of Transatlantic Letters. Janet Malcolm said Plath had the distinction of being, in her poetry, “never a nice person.” Ted Hughes said she had “a particular death-ray quality.”

Her first biographer, Edward Butscher, made a point to call her “the bitch goddess” (which he fully stole from William James). But Sylvia felt differently about herself, telling her therapist Ruth Beuscher in a 1962 letter that she was “a feeling & imaginative lay,” during a litany-like self-assessment as her marriage to Ted Hughes fell apart.

The world of Mean Girls implodes when Regina, discovering the cruel plots Cady and Janice have undertaken to bring her down, unleashes the Burn Book into their high school. The Burn Book is a secret book where The Plastics write down awful things about their classmates, teachers, and principal. Some of it is gossip; some just idle cruelty. There is at least one damaging, outright lie. But there is also the naming and exposure of sexual abuse— a teacher is sleeping with a student. Once that allegation turn out to be true, everything in the book gets investigated. But not before the school devolves into a full-scale riot, with young women violently going after one another. The girls have gone wild, a secretary says, in a clunky, dated reference to the videotape series. When Ariel was published in 1965, the girls, indeed, went wild. The book became a poetic banner for the burgeoning Second-Wave feminist movement, and the world wondered— Is it true? Ariel wasn’t idle gossip; it was a full-scale war on traditional notions of marriage, motherhood, and the pillowy bill of happy-ever-after goods the women’s magazines sold her generation. When her marriage tanked, Plath wasn’t buying that flaming pile of garbage anymore, and she said so in a way no one ever had before: Stop crying. Open your hand, Plath commands her reader in “The Applicant,” but she was more likely talking to herself: Get your shit together, Syl. Ted was a vampire and she had been a fool.

Put it in the book, sweetie.

As Mean Girls comes to an end, Regina gets hit by a bus and nearly dies. Sylvia, of course, didn’t survive to see her incredible success. As much as I love the film, I wish there was a more creative way to resolve it than to punish the beautiful girl with the nasty mouth, and venerate the smart one (who has to sacrifice being beautiful in order to make it). So much of the tension of Sylvia Plath’s life was pitched on the idea that she had to choose a single self— would she be blond and wild or dark-haired and scholarly? Was she a virgin or a slut? As I wrote back in 2017, when the internet had a solar meltdown over seeing Plath in a bikini on the cover of her first volume of Letters, I look to Plath for permission, “To be beautiful, and to be smart, and sexual, and to never, ever fall into the foolish trap that these cannot coexist.”

And for the record, Ted still can’t sit with us.