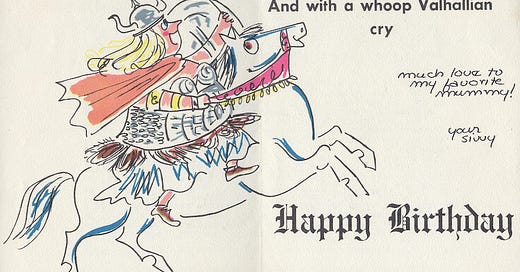

[Image description: A birthday card Sylvia Plath sent to her mother, Aurelia, with an illustration of a Viking woman riding a horse]

-For my friend Stephanie Cawley, another great Scorpio, another great poet, whose birthday is today

Yesterday would have been Sylvia Plath’s 89th birthday. As usual, I celebrated by writing and reading about her life and work. In this way, you could say every day is Sylvia Plath’s birthday for me, except it’s not. There is a particular energy I feel every October 27. I’m reminded that Plath should have lived a long life. In a letter she wrote to her therapist Ruth Beuscher on July 30, 1962, she said that by the time she was 50, she wanted “to be very experienced & have purple hair & be very wise & have interesting children & piles of money” (you can read this letter & many others, btw, in Plath’s second volume of Letters, published by Faber & Faber in England, and HarperCollins in the US). While much of my writing for this newsletter and elsewhere acts a kind of epistolary to Sylvia herself, I do actually love other, living writers, and sometimes I write to them. Most recently, I wrote to Maggie Nelson after reading her book The Argonauts, for the first time. The book reminded me— like Plath’s work does— that writing can be a wild act, a way to externalize the best & worst of what lives inside us, invisible to the world.

I told Dr. Nelson that I was “banging my head against the wall, trying to finish a book about Sylvia Plath,” and that her book had arrived like a gift. I wrote, “I never thought to want to write like Maggie Nelson because the whole world told me I needed to be Sylvia Plath. But of course, Sylvia Plath didn't want to be Sylvia Plath-- she wanted longevity and strangeness. Which I feel your writing helps make possible.” Imagine, though, Sylvia Plath getting the chance to write like Maggie Nelson, which is to say, imagine Sylvia Plath surviving. Not just the terrible winter of 1963, but the rest of a long, difficult, beautiful life, like so many people are granted. Imagine her, like Nelson, falling in love with a radical queer artist. Imagine her coming out. Imagine her joining a commune with a 12- and 10-year-old Frieda and Nick in tow, rolling their eyes at their mum’s ideals. Our straitjacketed images of Plath as a 1950s Golden Girl throwing herself at Ted Hughes, or a Zombie Queen poetess throwing it all on the pyre for the sake of her art do their work, and eke out these other possibilities. But remember that Sylvia was a contemporary of Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde, women who exploded their once-heteronormative lives in the late 1960s and 70s and became the face of radical gay and anti-racist writing. Remember, too, that Sylvia Plath was writing about queerness, in poems like “Lesbos” and, as Jacqueline Rose famously wrote, “The Rabbit Catcher,” among others.

If we think the idea of a queer Plath, or an activist Plath are crazy, there are reasons we think that way. We have been told those ideas are crazy by the men who knew Sylvia in her lifetime, and understood that knowledge and relationship as a form of ownership of her life and legacy, which they wielded with cultural force in the decades after her death. When Jacqueline Rose published The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, with its reading of Plath’s poem “The Rabbit Catcher” as being about bisexuality and oral sex, Ted Hughes went first on a private, then a public, grossly homophobic letter-writing campaign about how the mere reading of a poem as queer was “libelous.” His sister Olwyn later told Janet Malcolm that this reading libeled not only her brother, but also Sylvia Plath (“You can’t libel the dead,” Malcolm wearily responds).

What all of this points to is the immense power inherent to Sylvia’s work, and the ways people like Ted Hughes saw that as a threat they had to contain and control. “This is not easy poetry to criticize,” Hughes wrote of the 1965 UK edition of Ariel, in a short note that was sent out with the book when it was chosen for the Poetry Book Society. “It is just like her— but permanent.” On the surface, these sound like high compliments, and Hughes surely felt them to be that— he believed in his dead wife’s poems, just as he believed in them when she was living (there are a lot of people who think he was insanely envious of them, but that’s for another newsletter… and my book). But a closer look reveals the ways these comments turn Plath’s work and life into a frieze, and Ariel a quagmire rather than a work of imaginative literature. I won’t say that Plath’s work is “easy” to write about, per se, but it is a challenge that has become one of the great joys of my life. And its lack of permanence— the way the poems, novel, journals, stories, and letters— shift and swirl and seem, like a glamour, to reimagine themselves—is the reason we are still talking about Sylvia Plath today. It’s the reason that, in a single day, 60 strangers signed up for a newsletter about a woman who ended her life almost 60 years ago. Not because she ended her life, as we have too often been told, by everyone from the aforementioned Janet Malcolm to Sylvia Plath’s own daughter. But because she lived and wrote in a way that was unlike anyone we had encountered before. And because so many of us wanted to try and do the same.

Today is October 28. In the last year of her life, this wasn’t, for Sylvia Plath “the last October 28 I’ll ever see.” It was the day after she wrote “Ariel,” and dedicated it to her latest love interest, Al Alvarez. She was finishing up a month in which she wrote almost 30 new poems (yes, you read that right), many of which would become canonical in English literature. She was thinking of love, and London, looking to move back to the city and reclaim her life there. We have been taught to see Sylvia Plath’s life as a cautionary tale, but I think it the greatest gift, bringing me joy, making me friends, bringing me around the world for festivals, conferences, even a Fulbright scholarship. It trundles me ‘round the globe, as Sylvia wrote that famous, productive fall.

When Sylvia Plath drove Ted Hughes to the Exeter train station in October of 1962, so that he could move out of their shared home (and marriage) likely for good, she thought she was going to die of loneliness. Instead, she came home and wrote most of Ariel.

If that’s not an injunction to live like she did, what is?

![Bonhams : PLATH (SYLVIA) Birthday card to her mother with autograph message signed ("much love to my favourite mummy! your Sivvy"), with a long typed letter within, Friday, 24 April [1953] Bonhams : PLATH (SYLVIA) Birthday card to her mother with autograph message signed ("much love to my favourite mummy! your Sivvy"), with a long typed letter within, Friday, 24 April [1953]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kbpy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fefde6dd8-f8ac-477d-a8c0-eeda5eee64c8_960x647.jpeg)

Beautifully written and refreshes all of us Plath-philes who wonder "What if...?"

This essay arrived in my inbox when I needed it. Thank you, Emily and Sylvia (and Maggie Nelson).