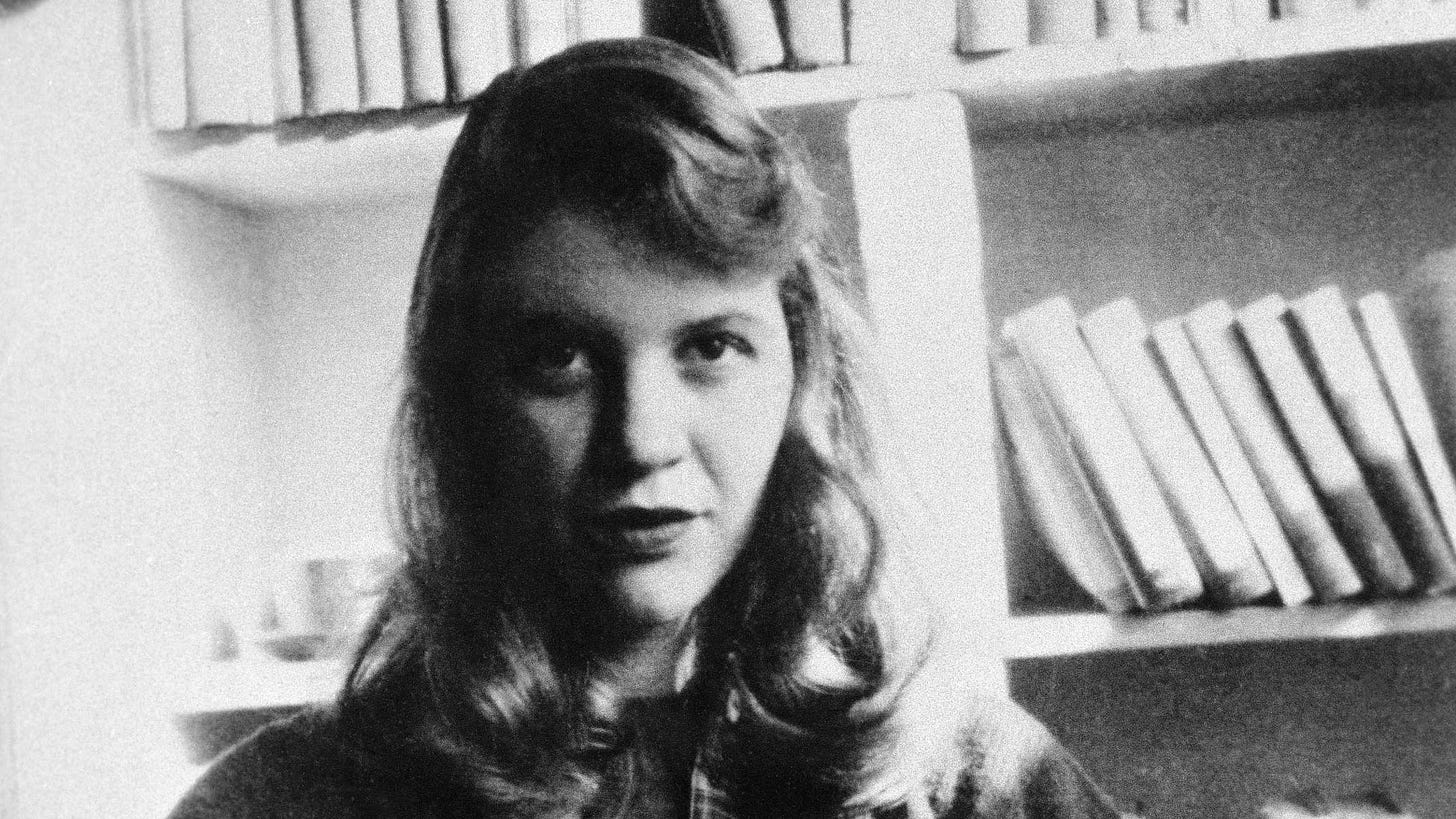

On October 21, 1962, Sylvia wrote her therapist-turned-confidante Ruth Beuscher a long letter in which, describing her writing, she said, “I have become a verb instead of an adjective.” About three months later, in a letter to her close friend Marcia Brown Stern, she took this a step further: “I feel like a very efficient tool or weapon,” she wrote. Although the phrase referred to motherhood, it’s hard not to apply it to Plath’s relationship with her poems from the time. Reading them, especially those very last poems from January and February 1963, I am reminded of the old joke about a small person walking a very large dog: Who’s walking who? Is Sylvia writing the poems or are the poems writing Sylvia?

I hesitate to write this. I am a proponent, above all, of Sylvia-as-human-woman. Why can’t we just deal with Plath as a writer, not a monster or a myth? Why is it so hard to accept that a suburban American woman wrote these poems? And yet, the night Plath died, she supposedly told her neighbor Trevor Thomas, the last person to see her, that she was having a wonderful dream, a vision. In her poem “Mystic” from January 1963, she wrote, “Once one has seen God, what is the remedy?” Whereas in “Elm,” an earlier poem, the speaker is only “inhabited by a cry,” the speaker in “Mystic” has been “seized up,” “used utterly.” She doesn’t have “a part left over.” These are the poems of a visionary, but for so long, we have been told that the vision is poison, that we do better to turn away.

Writing Loving Sylvia Plath means I can’t turn away, not only from the facts of Plath’s life and work but from the facts of my own. This is hardest not at the moment of writing, but instead in the middle of the night. As the mother of an infant, I am now, like Plath, up each morning at “the still, blue hour;” not to write, but to breastfeed my son. Or sometimes, to breastfeed my son and, as I obsess over the Gordian knot of Plath’s life and afterlife, of its complex relationship to my own and to so many women writers, to make book notes in my iPhone with one hand— one thumb!— while Bowie nurses. This is no cowlike maternity, as Plath said, but instead one compressed with endless work and edged with the thrill and terror of death. Outside the house, a pandemic continues to rage; inside, I am 41-years old, 11 years past Plath when she ended her life, and feel as though mine began only in the years since my children were born. Having outlived Plath, I long ago disabused myself of the notion I could ever write anything as good as she did. Instead of chasing her talent, I surrendered to it. In doing so, I may have saved my own life, but sometimes, as I ease the baby back to sleep and try to catch one more hour before it’s time to wake the big kids for school, I am drawn to the place between sleep and waking where language betrays me, where I know someday my breath will stop, my time will be up, and I will have nothing, or so much less than I once wanted, to show for it.

In the darkest of those hours, I turn toward Sylvia: poetry as meditation. Poetry as prayer. Stasis in darkness… I draw my breath in. I hear the silence. I hear a gunshot as the horse takes off. I let my breath out: Then the substanceless blue pour of tor and distances… Last night, trying to work out a section of the book on “Daddy” that’s giving me trouble, I heard her words in my head, in her voice, which is also somehow my voice: I thought every German was you/And the language obscene//An engine, an engine/Chuffing me off like a Jew.

An engine, an engine, I thought, I said, or my thoughts said: language becomes the vehicle that takes her away— takes the speaker away— how I resist this convention! It is her, it is she— it takes her away, Sylvia, the Sylvia of 1962, laughing as she reads the poem to Clarissa Roche in the drawing room of her Devon country home— but last night, too, it was me: an engine, I repeated, an engine, she repeated, and a blackness came through me, and of me, it was me, but also not me, and it carried me out, somewhere— not sleep, not waking, but to a foreign place, a language that chuffed me off, abandoned me and in its abandonment, made me. Was it Sylvia’s vision or my own? Who is making who?

It was a pleasure to read this. Really look forward to your book.

"My first book, The Colossus, I can't read any of the poems aloud now. I didn't write them to be read aloud. They, in fact, quite privately, bore me. These ones that I have just read, the ones that are very recent, I've got to say them, I speak them to myself, and I think that this in my own writing development is quite a new thing with me, and whatever lucidity they may have comes from the fact that I say them to myself, I say them aloud."

~ Peter Orr Interview